Why Strategy? The Mindset of Problem Solving.

“Without strategy you just have a list of things you wish would happen.” – Richard Rumelt

In his book Good Strategy Bad Strategy, Richard Rumelt discusses the concept of bad strategy, telling tales of failed military attacks or quarterbacks whose strategy is to “JUST WIN.” He unpacks the language of broad goals, ambition, vision, and values. In the brand world, each of these elements is, of course, an important part of a well-formed brand. But by themselves, they are not substitutes for the hard work of strategy.

Although Rumelt discusses strategy within the context of large corporate operations and business, strategy in brand and communications isn’t really all that different.

A good strategy is an approach to overcoming an obstacle, a response to a challenge or problem. If the problem is not defined, it is difficult or impossible to assess the quality of the strategy and near impossible to execute against it.

Which brings us to the four tenets of good strategy:

- a good brief;

- a well-defined problem;

- an insight to unlock the problem; and

- an advantage that positions you to solve the problem.

Writing good briefs

The role of a good brief is often underestimated. We often have client briefs come in that are very prescriptive. That is, coming to us with a solution already in mind, or a list of deliverables. Now, clients of course know their business. But as consultants, advisors, and creative partners – we are naturally curious. We are biting at your heels to ask questions.

We often get asked to solve marketing and communications problems, but the better question is – what is the outcome you want to achieve? What is the problem within the problem?

We want to go three-why’s-deep. Asking “why, but why? BUT WHY?” isn’t to probe senselessly, but to reveal a much deeper and specific issue. Briefing an agency is an opportunity to create a deeper understanding of what is required to move the needle. To be effective.

Defining the problem correctly

“If I were given one hour to save the planet, I would spend 59 minutes defining the problem and one minute resolving it.” – Albert Einstein

Defining the right problem is the most difficult and the most important of all the steps. It involves diagnosing the situation so that we focus on the real problem and not on its symptoms.

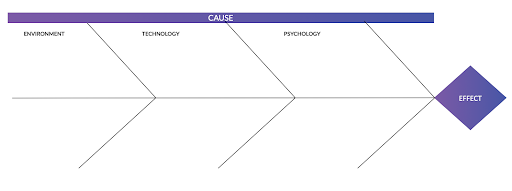

A fishbone is something typically used in business consulting. It’s a tool that explains the cause and effect relationship behind a problem. It provides the visual representation of all the possible causes of a problem to analyze and find out the root cause. It can also help you to determine a more robust and accurate problem, understanding the full nature of the challenge.

The more accurate the problem, the higher the likelihood of finding a solution that works.

There are varying models of this, with varying degrees of complexity. But the point is, the further you dive into the cause and effect relationship the closer you are to defining the most accurate problem.

Unlocking the problem, seeing things in a new light

Once you have a well-defined problem, you can then find ways to look at the problem in a new way. An insight is a way to unlock a problem. It is an opportunity to identify ways to solve it.

In creative problem solving there are lots of ways to find insights.

A diagnosis is the problem behind the problem. We’ve lost 10% of chewing gum purchases at the till. The real problem is it’s 2024 and people standing in line are staring at their phones rather than marketing displays.

A flip is the opposite of a norm or a cliché. Man buns are for hipsters who don’t conform. The flip? Man buns actually group you, which can appear to conform you.

A spanner is an observation followed by a “but” or “because.” Not dissimilar to ‘three why’s deep,’ it’s following an observation with a deeper observation. People don’t save for retirement because they don’t think about how long they will live after they retire. Observation: anti-smoking ads for teens don’t work. Deeper observation: anti-smoking ads for teens don’t work because most teens reject authority. (It’s not really even about smoking.)

A reframe takes an understanding and reframes it to view it afresh. It’s taking an understanding of something, pausing, and looking at it more closely. Or, looking at it from a different perspective, maybe considering your blind spots, or biases. Example: just because you’re sick, it doesn’t mean you’re weak.

The makeup of a good insight

A good insight should:

- Be anchored in a deep understanding of the market.

- Be forward looking, built on connecting multiple sources of information.

- Go beyond facts to explain the why of customer behaviour.

- Bring a new understanding to bear on issues and challenge existing beliefs.

- Be relevant and lead to action; otherwise it’s not an insight, it’s just information.

A bad insight:

- Is all about the brand, business, or product.

- Conflates multiple concepts or ideas at once.

- Sounds the same as someone else or something that’s already been done.

- Overly relies on data or, worse, thinking data alone is an insight.

- Is only an observation; an observation tells us what happened, not why.

Establishing an advantage

It’s all well and good to spot an insight, or a new way of looking at the problem. But unless you actually have what it takes to back up your solution, you don’t have an advantage. Your advantage is what makes your brand unique or aptly set up to respond to the problem. Your advantage is your proof points. Why should people believe this? (If you can’t write this, it’s likely not true, and then you can’t really say it. Abort.)

The formula of strategy

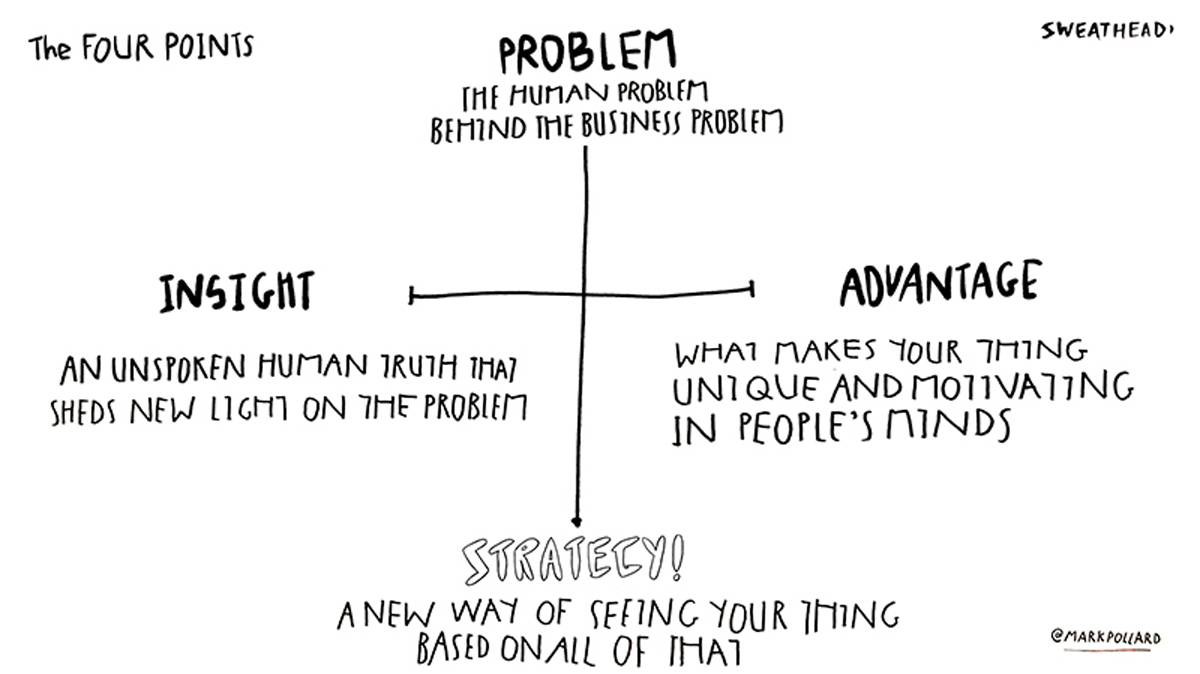

Problem + problem behind the problem + insight that unlocks the problem + an advantage that positions you to solve the problem = strategy. One great example of how this might look as a framework is the Four Points theory from strategy CEO Mark Pollard.

Strategy as a mindset

It certainly is not just ‘the thing in the middle’ before creativity starts. Strategy isn’t a thing we do, it’s the thing. It’s an entire mentality.

It’s asking the right questions. It’s interrogating the status quo. It’s challenging the brief. It’s diving deeper into problems. It’s being brave or thinking heretically. It is not turning away from awkward pauses in a meeting but leaning into them and asking why? It’s knowing that sometimes less is more. It’s knowing that good strategy is subjective. It’s knowing that good ideas can come from anywhere.

It’s knowing that there are three sins in uncovering, writing, and executing against a strategy…

Lying, copying, and being boring.